L. H. Draken interview

The number of new Art of War editions over the last decade has proliferated. Almost all of them are mere copy-and-paste versions of the Giles edition, which has become public domain. It has gotten so bad Sonshi.com's default policy is to ignore new publications of Sun Tzu's Art of War.

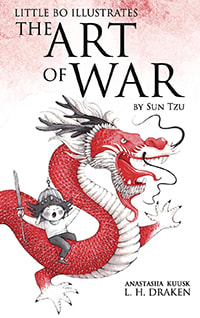

So it was much to our delight to discover an extraordinary Art of War edition that instantly caught our attention: Little Bo Illustrates The Art of War. The book's illustrations -- from little Bo's cat to little Bo reading his Art of War book -- all drawn by Anastasiia Kuusk are amazing to behold. The detailed ink-and-watercolor visuals alone would be worth owning the book, but wait there's more. Little Bo of course quotes Sun Tzu but his words also come from a talented crime fiction author, L. H. Draken.

L. H. Draken's life and personality represent the dichotomous concepts found in Sun Tzu's Art of War:

Most of all, Ms. Draken represents well the extraordinary balance between East and West, not only being able to understand each side but also being able to create sense and unity with both. It is this extraordinary balance we at Sonshi seek in the classics like The Art of War. It is this extraordinary balance we see in refined individuals like L. H. Draken.

Below is our interview with L. H. Draken. Enjoy!

So it was much to our delight to discover an extraordinary Art of War edition that instantly caught our attention: Little Bo Illustrates The Art of War. The book's illustrations -- from little Bo's cat to little Bo reading his Art of War book -- all drawn by Anastasiia Kuusk are amazing to behold. The detailed ink-and-watercolor visuals alone would be worth owning the book, but wait there's more. Little Bo of course quotes Sun Tzu but his words also come from a talented crime fiction author, L. H. Draken.

L. H. Draken's life and personality represent the dichotomous concepts found in Sun Tzu's Art of War:

- She studied High Energy physics but writes fiction.

- She spurned learning the German language but ended up marrying a German man, worked for a German company, and now lives in Germany.

- She writes about serious matters like crime but her writings are sprinkled with witty humor.

Most of all, Ms. Draken represents well the extraordinary balance between East and West, not only being able to understand each side but also being able to create sense and unity with both. It is this extraordinary balance we at Sonshi seek in the classics like The Art of War. It is this extraordinary balance we see in refined individuals like L. H. Draken.

Below is our interview with L. H. Draken. Enjoy!

Sonshi: You and your husband lived in Beijing for five years. How has the experience changed your approach to writing and life in general?

Draken: That’s a rather complicated question that could be a whole interview by itself.

One of the simpler answers might be that it motivated me to take writing seriously to start with. I lived there at a time when I was done with studying and all of a sudden had my evenings and weekends to myself — which helped. It was also when we had our first son, which meant my normal 9-5 hours changed, which can also be a motivation for using time better/differently.

But besides personal changes, China was a huge experience, all by itself. Living there made me realize how little we understand about the country with arguably the biggest influence on world politics and economics next to the United States. For a long time, China has played a rather closed role on the world stage, choosing to not actively participate in world affairs and keeping its economy closed off to the rest of the world. But in the last twenty years the economy side has drastically changed, and in the very recent years, the politics portion has also shifted. And yet the key statement, that we understand so little about China, is still the same.

When we lived there I felt like I was getting all these amazing interactions with the drama and culture of China, which went a long way to understanding the motivations of how people there think and how the country works, all of which I’d never understood before from the simple news stories that make it to American media and the pop-culture Kung-Fu sort of stuff seen on TV.

I started off carrying some of this into a blog — but that flopped pretty quick. I think the expectation wasn’t high enough for me to write on it consistently. And perhaps worse, there are so many expats who write blogs while living in China (or abroad) that it didn’t feel like I was filling an unmet need.

There’s something else though, that people sometimes ask, ‘why a thriller’, and that answer dovetails with how I got to write my first book, (a thriller set in Beijing) — the life and culture of living in China lends itself to a thriller/mystery. There is so much that happens in the politics behind closed doors, not just stuff we as foreigners don’t see, but which the average citizen is excluded from understanding. No one knows, for instance, precisely how the General Secretary is decided. We assume it’s from some machinations of the Politburo (the nine men who make up the head positions of what we’d call a cabinet, in the US), but there’s no official vote or even white paper that outlines how that decision is made.

On top of this, there are all sorts of rumors and tales that circle around the community about people who’ve disappeared or been taken to a black prison (unofficial detention centers). There’s just a lot there that lends itself to the story of a Thriller.

And that’s how I got into writing real books. There aren’t many people writing thrillers based in China, and not currently in Beijing (as far as I know). I felt like there is a need for people to understand how things are working in China and what the issues and mindset of the local Chinese are. So with that expectation in mind, I started writing.

Sonshi: Your new book, Little Bo Illustrates The Art of War, will be coming out on October 1! It's a children's book. We can't wait to read it! There was an outstanding illustrated version of Sun Tzu's Art of War by Tsai Chih Chung many years ago but the illustrations in your book looks absolutely stunning. Tell us about your illustrator Anastasiia Kuusk and how you both got together and collaborated on the book.

Draken: To be honest, I’m a little hesitant to say it’s a Children’s book. I have two children, and although they surely enjoy the drawings, the text itself is rather dense for a child — it’s still direct quotes from Sun Tzu. I think of it more as a novelty book which adults might enjoy, the way many still read comic books. But yes, I’m super excited for its release in October as well.

Anastasiia did a really beautiful job with the drawings. I first hired her from a work-sharing site where you post a job you need done, and different artists and contract workers can apply to do the work for you. The particular job was to draw/paint my Christmas card that December. She did such a beautiful job that come January, I invited her to work on this project.

We worked together discussing what sort of stories and illustrations we wanted to match to the different quotes. I let her choose some of the quotes she felt drawn to, and I suggested ones I thought lent themselves to certain ideas or events for me. It was a lot of fun to imagine how to illustrate Sun Tzu’s work. She’d sketched some ideas and we’d go over them again trying to get the idea just right. Lots of back and forth. In the end, I think we both felt really quite satisfied with how she applied her amazing skill and brush.

Anastasiia has done a couple of children books already, you can find some of her work on Instagram @anastasiia_kuusk_art. She does really beautiful work.

Sonshi: When did you first learn about Sun Tzu's Art of War? What about the book made you continue to study it and now publish a book about it?

Draken: I couldn’t say when I first learned about Sun Tzu’s work. I’ve known about its existence for quite a long time — it’s one of those classics of which you’re aware and might superficially read in school, but don’t necessarily know well.

I believe honestly, one aspect that drew me to use it for this sort of project was the fantastic title. War being something we think of as very dark and serious, and Art being something quite imaginative and inexplicable. And yet, both are practices that are serious and have rules and strategies associated with them. To study the practice of war as an art form really appealed to me, especially how Sun Tzu does it, applying human psychology and the stratagems of how you treat people and how what you should expect from yourself as a leader to how you interact with people, especially people with whom you might have serious disagreements. It’s very poetic and yet quite serious and more than 2500 years later, so applicable.

I particularly liked then contrasting this serious and ‘adult’ subject, with illustrations of a young boy, and his struggle in learning how to act correctly. That’s what childhood is, isn’t it; turning a wild creature into someone who knows the rules and expectations of human interaction and society, so they know how best to behave and participate. (I take the liberty to say, ‘wild creature’, only because I’m blessed to have two of my own). The illustrations aren’t one coherent story, but sort of grouped together as various incidents, micro stories, that illustrate how Little Bo sometimes gets it right, and often gets it wrong, in his applications of Sun Tzu’s wisdom.

Sonshi: What is your favorite quote from Sun Tzu's Art of War? Why do you like it?

Draken: An obvious, but tough question! It’s safe to say I used all my favorites in the book. But narrowing it down to one…

From the big-picture side of things, I’d say something like a quote I use early in the book.

If you know the enemy and know yourself, you need not fear the result of a hundred battles.

It appeals to me on a Socratic level. It speaks to knowing yourself, and how important it is to first know who you are and what you are capable of before you go out and engage with others, especially an enemy. The human person is an incredibly complex and not at all intuitive creature, so this first part takes that into account, adding on top that you have to also know your enemy, I would argue that you have to know the enemy then better than you know yourself (which really seems impossible). But then that this knowledge, the truth, or reality or ‘how things really are’, means you needn’t act in fear. It doesn’t say, ‘know yourself and you’ll always win’, or ‘know your enemy and you’ll be able to manipulate him into submission’. It simply says, ‘know yourself, and your enemy and you need not fear any battle.’

That’s wisdom. Because you may know yourself, and know your enemy and know there is no way to expect victory, and yet you still might have to move into battle. The Spartans knew they would die, to the last man, at the battle of Thermopylae, and yet somehow they fought anyway. That’s knowing yourself, and knowing your enemy.

I don’t believe in niece optimism, or that knowledge of truth brings you a magic weapon that means you’ll always be victorious. But I do believe that knowledge and acting in truth means we do not need to act in fear. And that knowing the truth, and acting in truth, results in the best possible outcome. That still may not be a great outcome, but it’s without a doubt, the best one available.

Sonshi: Although Sun Tzu's Art of War originated in China, the book belongs to the world. The reason why we say this is The Art of War is read and studied throughout the world. It has been adopted by other Asian countries like Japan for centuries. Singapore's leaders love The Art of War. In the US, all officers in the US Marine Corps are required to read The Art of War, and it is the book of choice of at least two former US Secretaries of Defense, Bob Gates and Jim Mattis. So our next question might seem surprising: Do you think China's leadership is studying and applying Sun Tzu's Art of War well?

Draken: This question made me laugh a little, because I was just talking to a translator friend of mine, a German who has done some work interpreting for delegations between Germans and Chinese military officials. He said the Germans were quoting Sun Tzu and the Chinese were quoting Clausewitz, a Prussian military theorist. Probably this goes more to the earlier quote about knowing your enemy than it does to what the Chinese are studying and applying in their own politics (and not to make any sort of side statement about Germans and Chinese being enemies!).

It’s hard, in my opinion, to say what Chinese leadership is studying — again, we return to the topic of much of what they do being behind closed doors. I wouldn’t be able to make a meaningful statement about what texts they use in their political training or bootcamps. Although in my opinion they do tend to be very proud of their own and revere their masters (and rightly so, as they have some very impressive men among their ranks of history).

At the same time, the lessons of Sun Tzu are interwoven with so much modern theory and strategy that I don’t think one can separate him from more modern strategists. What would be Sun Tzu and what is Napoleon, if Napoleon studied Sun Tzu?

But applying this question in a different way, if you’re asking for a statement on how Chinese politicians and the Chinese military act in modern times—I would say that the Chinese are extremely strategic about how they make decisions and how they go about pursuing long term goals. This is something I think they have as an advantage in their governmental system. So much of how a decision in the US is made seems to be directly linked to what moment we’re at in the election cycle. And these days, a four-year election cycle is quite short (for the president, obviously it is different for congress people, but the same logic applies). It is one of the built-in short comings of a republic that elects its leaders and where the leaders have really fairly limited power. The Chinese are much better at making 5-year plans and implementing them over longer cycles. 5-year, 10-year, 50-year plans — all a core part of Chinese political strategy, and all something western republics can’t really implement over longer periods when the governing body changes much more frequently.

Whatever the Chinese study, and surely it is indeed also Sun Tzu, they are very strategic in ‘knowing their enemy’ and calculating where to ‘strike at that which is weak and avoid that which is strong’.

Sonshi: Tell us more about your first book, The Year of the Rabid Dragon, and its protagonist Nathan Troy!

Draken: The Art of War is more of a passion project, albeit one that took much of my focus for the last few months. I actually started it when my second son was born; people gave me small bits of cash as a baby present, not knowing what I needed for the baby since he was our second. I didn’t need very much (one needs much less for babies than one expects!) So I took the money and used it to hire an illustrator to draw a book, which I then dedicated to my sons. But thrillers and crime is really where I spend most of my time.

The Year of the Rabid Dragon is a medical thriller, based in Beijing, in 2012 (as the name implies, if you know a little about the Chinese Zodiac). It was a lot of fun to write because I was able to pull in so much of my daily experience in China. The characters I met on the street, the people with whom I worked, the stories that floated around in the local papers and among the expats. It’s really a snapshot of Beijing, 2012. Interestingly enough, China has really changed since we left, I think largely due to the leadership that changed in the fall of 2012, and so Beijing is a different city than what I describe in the book. Many of the locations I used or the small things Nathan comments on (the different street food, for example), is no longer part of daily life in Beijing. So I think it’s sort of a cool time-piece. I think the politics and ‘feel’ of the city is different now, so if I write a book based in 2019 or ’20, I’d have to move back.

The story itself explores what could happen when you take the ethics of Beijing politics, and apply it to a technology like gene-editing. CRISPR had just started to make headlines, in a small way, when I was living there. It’s the sort of crazy and fantastical tool that is so simple and might lead so many different ways. It lends itself to a good medical mystery. In the book I was also really interested in exploring the different moral code that Beijing applies to its politics and decision making. People often make the assumption that Beijing Politics are the result of Mao Zedong and the Cultural Revolution and Communism. Of course there is a large part of that. But in my opinion, the reason Communism and Marxist philosophy was such a lasting fit in China is because it matches up with some much older ideas that were already core principles in Chinese culture. The Confucian ideas of the group (elders, society) taking precedent over the individual, for instance. That the individual is valuable as he contributes to the furtherance of the needs of the family and larger society. Which can be adopted quite well into the Communist manifesto of the needs of the group outweighing the needs of the individual.

So take an idea like that (the different moral code) and a technology like gene editing, CRISPR, and one can see how Chinese scientists and government policy might support risky endeavors in pursuit of a goal for the larger body, even if the early individuals might suffer or even die as a result.

Western scientists currently still say CRISPR is really too young a technology to do some of the more daring tests Chinese have already done (in 2018, even, as my book was just getting published, Chinese scientist He Jiankui announced he’d successfully edited the genome of twin baby girls!). But if you think this tool could cure AIDS, for instance, then the risk for a few individuals is small compared to the benefit for all society.

Of course, my book takes the ideas to a darker place—it is a thriller, after all.

I’m two thirds into the sequel and have a few more adventures up my sleeve for Nathan, so I’m really excited about sharing more of him with readers in the future.

Sonshi: What's more difficult: physics or writing?

Draken: Depends on which activity I find myself doing. When I was in Physics, I suppose I thought physics was more difficult. But there’s that great quote from Hemingway, ‘There’s nothing to writing, all you do is sit down at the typewriter and bleed.’ Writing certainly isn’t easy either.

I think all creative endeavors are difficult, because you’re pulling out of the ether something that didn’t exist before. That’s damn hard! Good physics is a creative endeavor, because you’re solving a problem that hasn’t yet been solved. You’re essentially inventing something new. Good writing is the same thing. I love both but I think I’m better suited to being a good writer, so perhaps that’s easier. Although that’s not always obvious to me.

[End of interview]

Draken: That’s a rather complicated question that could be a whole interview by itself.

One of the simpler answers might be that it motivated me to take writing seriously to start with. I lived there at a time when I was done with studying and all of a sudden had my evenings and weekends to myself — which helped. It was also when we had our first son, which meant my normal 9-5 hours changed, which can also be a motivation for using time better/differently.

But besides personal changes, China was a huge experience, all by itself. Living there made me realize how little we understand about the country with arguably the biggest influence on world politics and economics next to the United States. For a long time, China has played a rather closed role on the world stage, choosing to not actively participate in world affairs and keeping its economy closed off to the rest of the world. But in the last twenty years the economy side has drastically changed, and in the very recent years, the politics portion has also shifted. And yet the key statement, that we understand so little about China, is still the same.

When we lived there I felt like I was getting all these amazing interactions with the drama and culture of China, which went a long way to understanding the motivations of how people there think and how the country works, all of which I’d never understood before from the simple news stories that make it to American media and the pop-culture Kung-Fu sort of stuff seen on TV.

I started off carrying some of this into a blog — but that flopped pretty quick. I think the expectation wasn’t high enough for me to write on it consistently. And perhaps worse, there are so many expats who write blogs while living in China (or abroad) that it didn’t feel like I was filling an unmet need.

There’s something else though, that people sometimes ask, ‘why a thriller’, and that answer dovetails with how I got to write my first book, (a thriller set in Beijing) — the life and culture of living in China lends itself to a thriller/mystery. There is so much that happens in the politics behind closed doors, not just stuff we as foreigners don’t see, but which the average citizen is excluded from understanding. No one knows, for instance, precisely how the General Secretary is decided. We assume it’s from some machinations of the Politburo (the nine men who make up the head positions of what we’d call a cabinet, in the US), but there’s no official vote or even white paper that outlines how that decision is made.

On top of this, there are all sorts of rumors and tales that circle around the community about people who’ve disappeared or been taken to a black prison (unofficial detention centers). There’s just a lot there that lends itself to the story of a Thriller.

And that’s how I got into writing real books. There aren’t many people writing thrillers based in China, and not currently in Beijing (as far as I know). I felt like there is a need for people to understand how things are working in China and what the issues and mindset of the local Chinese are. So with that expectation in mind, I started writing.

Sonshi: Your new book, Little Bo Illustrates The Art of War, will be coming out on October 1! It's a children's book. We can't wait to read it! There was an outstanding illustrated version of Sun Tzu's Art of War by Tsai Chih Chung many years ago but the illustrations in your book looks absolutely stunning. Tell us about your illustrator Anastasiia Kuusk and how you both got together and collaborated on the book.

Draken: To be honest, I’m a little hesitant to say it’s a Children’s book. I have two children, and although they surely enjoy the drawings, the text itself is rather dense for a child — it’s still direct quotes from Sun Tzu. I think of it more as a novelty book which adults might enjoy, the way many still read comic books. But yes, I’m super excited for its release in October as well.

Anastasiia did a really beautiful job with the drawings. I first hired her from a work-sharing site where you post a job you need done, and different artists and contract workers can apply to do the work for you. The particular job was to draw/paint my Christmas card that December. She did such a beautiful job that come January, I invited her to work on this project.

We worked together discussing what sort of stories and illustrations we wanted to match to the different quotes. I let her choose some of the quotes she felt drawn to, and I suggested ones I thought lent themselves to certain ideas or events for me. It was a lot of fun to imagine how to illustrate Sun Tzu’s work. She’d sketched some ideas and we’d go over them again trying to get the idea just right. Lots of back and forth. In the end, I think we both felt really quite satisfied with how she applied her amazing skill and brush.

Anastasiia has done a couple of children books already, you can find some of her work on Instagram @anastasiia_kuusk_art. She does really beautiful work.

Sonshi: When did you first learn about Sun Tzu's Art of War? What about the book made you continue to study it and now publish a book about it?

Draken: I couldn’t say when I first learned about Sun Tzu’s work. I’ve known about its existence for quite a long time — it’s one of those classics of which you’re aware and might superficially read in school, but don’t necessarily know well.

I believe honestly, one aspect that drew me to use it for this sort of project was the fantastic title. War being something we think of as very dark and serious, and Art being something quite imaginative and inexplicable. And yet, both are practices that are serious and have rules and strategies associated with them. To study the practice of war as an art form really appealed to me, especially how Sun Tzu does it, applying human psychology and the stratagems of how you treat people and how what you should expect from yourself as a leader to how you interact with people, especially people with whom you might have serious disagreements. It’s very poetic and yet quite serious and more than 2500 years later, so applicable.

I particularly liked then contrasting this serious and ‘adult’ subject, with illustrations of a young boy, and his struggle in learning how to act correctly. That’s what childhood is, isn’t it; turning a wild creature into someone who knows the rules and expectations of human interaction and society, so they know how best to behave and participate. (I take the liberty to say, ‘wild creature’, only because I’m blessed to have two of my own). The illustrations aren’t one coherent story, but sort of grouped together as various incidents, micro stories, that illustrate how Little Bo sometimes gets it right, and often gets it wrong, in his applications of Sun Tzu’s wisdom.

Sonshi: What is your favorite quote from Sun Tzu's Art of War? Why do you like it?

Draken: An obvious, but tough question! It’s safe to say I used all my favorites in the book. But narrowing it down to one…

From the big-picture side of things, I’d say something like a quote I use early in the book.

If you know the enemy and know yourself, you need not fear the result of a hundred battles.

It appeals to me on a Socratic level. It speaks to knowing yourself, and how important it is to first know who you are and what you are capable of before you go out and engage with others, especially an enemy. The human person is an incredibly complex and not at all intuitive creature, so this first part takes that into account, adding on top that you have to also know your enemy, I would argue that you have to know the enemy then better than you know yourself (which really seems impossible). But then that this knowledge, the truth, or reality or ‘how things really are’, means you needn’t act in fear. It doesn’t say, ‘know yourself and you’ll always win’, or ‘know your enemy and you’ll be able to manipulate him into submission’. It simply says, ‘know yourself, and your enemy and you need not fear any battle.’

That’s wisdom. Because you may know yourself, and know your enemy and know there is no way to expect victory, and yet you still might have to move into battle. The Spartans knew they would die, to the last man, at the battle of Thermopylae, and yet somehow they fought anyway. That’s knowing yourself, and knowing your enemy.

I don’t believe in niece optimism, or that knowledge of truth brings you a magic weapon that means you’ll always be victorious. But I do believe that knowledge and acting in truth means we do not need to act in fear. And that knowing the truth, and acting in truth, results in the best possible outcome. That still may not be a great outcome, but it’s without a doubt, the best one available.

Sonshi: Although Sun Tzu's Art of War originated in China, the book belongs to the world. The reason why we say this is The Art of War is read and studied throughout the world. It has been adopted by other Asian countries like Japan for centuries. Singapore's leaders love The Art of War. In the US, all officers in the US Marine Corps are required to read The Art of War, and it is the book of choice of at least two former US Secretaries of Defense, Bob Gates and Jim Mattis. So our next question might seem surprising: Do you think China's leadership is studying and applying Sun Tzu's Art of War well?

Draken: This question made me laugh a little, because I was just talking to a translator friend of mine, a German who has done some work interpreting for delegations between Germans and Chinese military officials. He said the Germans were quoting Sun Tzu and the Chinese were quoting Clausewitz, a Prussian military theorist. Probably this goes more to the earlier quote about knowing your enemy than it does to what the Chinese are studying and applying in their own politics (and not to make any sort of side statement about Germans and Chinese being enemies!).

It’s hard, in my opinion, to say what Chinese leadership is studying — again, we return to the topic of much of what they do being behind closed doors. I wouldn’t be able to make a meaningful statement about what texts they use in their political training or bootcamps. Although in my opinion they do tend to be very proud of their own and revere their masters (and rightly so, as they have some very impressive men among their ranks of history).

At the same time, the lessons of Sun Tzu are interwoven with so much modern theory and strategy that I don’t think one can separate him from more modern strategists. What would be Sun Tzu and what is Napoleon, if Napoleon studied Sun Tzu?

But applying this question in a different way, if you’re asking for a statement on how Chinese politicians and the Chinese military act in modern times—I would say that the Chinese are extremely strategic about how they make decisions and how they go about pursuing long term goals. This is something I think they have as an advantage in their governmental system. So much of how a decision in the US is made seems to be directly linked to what moment we’re at in the election cycle. And these days, a four-year election cycle is quite short (for the president, obviously it is different for congress people, but the same logic applies). It is one of the built-in short comings of a republic that elects its leaders and where the leaders have really fairly limited power. The Chinese are much better at making 5-year plans and implementing them over longer cycles. 5-year, 10-year, 50-year plans — all a core part of Chinese political strategy, and all something western republics can’t really implement over longer periods when the governing body changes much more frequently.

Whatever the Chinese study, and surely it is indeed also Sun Tzu, they are very strategic in ‘knowing their enemy’ and calculating where to ‘strike at that which is weak and avoid that which is strong’.

Sonshi: Tell us more about your first book, The Year of the Rabid Dragon, and its protagonist Nathan Troy!

Draken: The Art of War is more of a passion project, albeit one that took much of my focus for the last few months. I actually started it when my second son was born; people gave me small bits of cash as a baby present, not knowing what I needed for the baby since he was our second. I didn’t need very much (one needs much less for babies than one expects!) So I took the money and used it to hire an illustrator to draw a book, which I then dedicated to my sons. But thrillers and crime is really where I spend most of my time.

The Year of the Rabid Dragon is a medical thriller, based in Beijing, in 2012 (as the name implies, if you know a little about the Chinese Zodiac). It was a lot of fun to write because I was able to pull in so much of my daily experience in China. The characters I met on the street, the people with whom I worked, the stories that floated around in the local papers and among the expats. It’s really a snapshot of Beijing, 2012. Interestingly enough, China has really changed since we left, I think largely due to the leadership that changed in the fall of 2012, and so Beijing is a different city than what I describe in the book. Many of the locations I used or the small things Nathan comments on (the different street food, for example), is no longer part of daily life in Beijing. So I think it’s sort of a cool time-piece. I think the politics and ‘feel’ of the city is different now, so if I write a book based in 2019 or ’20, I’d have to move back.

The story itself explores what could happen when you take the ethics of Beijing politics, and apply it to a technology like gene-editing. CRISPR had just started to make headlines, in a small way, when I was living there. It’s the sort of crazy and fantastical tool that is so simple and might lead so many different ways. It lends itself to a good medical mystery. In the book I was also really interested in exploring the different moral code that Beijing applies to its politics and decision making. People often make the assumption that Beijing Politics are the result of Mao Zedong and the Cultural Revolution and Communism. Of course there is a large part of that. But in my opinion, the reason Communism and Marxist philosophy was such a lasting fit in China is because it matches up with some much older ideas that were already core principles in Chinese culture. The Confucian ideas of the group (elders, society) taking precedent over the individual, for instance. That the individual is valuable as he contributes to the furtherance of the needs of the family and larger society. Which can be adopted quite well into the Communist manifesto of the needs of the group outweighing the needs of the individual.

So take an idea like that (the different moral code) and a technology like gene editing, CRISPR, and one can see how Chinese scientists and government policy might support risky endeavors in pursuit of a goal for the larger body, even if the early individuals might suffer or even die as a result.

Western scientists currently still say CRISPR is really too young a technology to do some of the more daring tests Chinese have already done (in 2018, even, as my book was just getting published, Chinese scientist He Jiankui announced he’d successfully edited the genome of twin baby girls!). But if you think this tool could cure AIDS, for instance, then the risk for a few individuals is small compared to the benefit for all society.

Of course, my book takes the ideas to a darker place—it is a thriller, after all.

I’m two thirds into the sequel and have a few more adventures up my sleeve for Nathan, so I’m really excited about sharing more of him with readers in the future.

Sonshi: What's more difficult: physics or writing?

Draken: Depends on which activity I find myself doing. When I was in Physics, I suppose I thought physics was more difficult. But there’s that great quote from Hemingway, ‘There’s nothing to writing, all you do is sit down at the typewriter and bleed.’ Writing certainly isn’t easy either.

I think all creative endeavors are difficult, because you’re pulling out of the ether something that didn’t exist before. That’s damn hard! Good physics is a creative endeavor, because you’re solving a problem that hasn’t yet been solved. You’re essentially inventing something new. Good writing is the same thing. I love both but I think I’m better suited to being a good writer, so perhaps that’s easier. Although that’s not always obvious to me.

[End of interview]