Peter Harris interview

Peter Harris, translator

Peter Harris, translator

We are naturally skeptical when new Sun Tzu's Art of War editions come out. For the past few years, they are almost always rehashed versions of a public domain translation with little additional scholarly material. The last time Sonshi recommended an Art of War book was in 2007, over a decade ago.

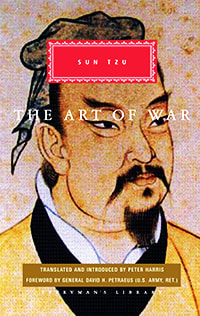

Today, we are honored and thrilled to recommend to you a new Art of War edition worthy of your time and study: Sun Tzu: The Art of War translated by Peter Harris with a Foreword by Gen. David H. Petraeus, published on March 13, 2018, by the venerable Everyman's Library.

A written review of this new translation is forthcoming and will soon be included in our recommendations page, but in the meantime, we would like to introduce you to Peter Harris, an experienced specialist in governance reform, international relations and political and cultural history, with particular reference to China and its neighboring countries.

Born and raised in England, Harris is the Senior Fellow of the New Zealand Contemporary China Research Centre at Victoria University of Wellington, and an Honorary Member of the China Studies Centre at the University of Sydney, Australia.

He was Visiting Professor at the School of Foreign Studies at Nanjing University, Nanjing, China, Director of Asian Studies at Victoria, Senior Fellow at the Centre for Strategic Studies at Victoria, Representative of the Ford Foundation in China, founding Director of the Asia New Zealand Foundation, head of the BBC Chinese Service, and head of Asia research at the International Secretariat of Amnesty International.

He earned a BA (1st Class Honors) in Chinese and an M Phil in International Relations from the University of Oxford.

Peter Harris has published widely on Chinese and Asian affairs in numerous books and scholarly articles. They include China at the Crossroads: What the Third Plenum means for China, New Zealand and the World (Wellington: Victoria University Press for the New Zealand Contemporary China Research Centre, 2014), Concept Papers and Opinion Brochures on Key Democratic Reform Issues(Almaty and Washington DC: USAID and Counterpart, 2010), Three Hundred Tang Poems (London and New York: Penguin Random House/Alfred A Knopf, 2009), The Travels of Marco Polo (London and New York: Penguin Random House/Alfred A Knopf, 2008), and Zhou Daguan’s Record of Cambodia: The Land and its People (Chiang Mai: Silkworm Press with the University of Washington Press, Seattle, 2007). Zhou Daguan’s Record of Cambodia, on a Chinese envoy’s first-hand account of the civilization of Angkor, was named an Outstanding Academic Title for 2008 by the US scholarly journal Choice.

He is currently working on a new annotated translation of the Chinese reformer Liang Qichao's The Doctrine of Renewing the People (xin min shuo) in collaboration with Yi Diandian and others.

Today, we are honored and thrilled to recommend to you a new Art of War edition worthy of your time and study: Sun Tzu: The Art of War translated by Peter Harris with a Foreword by Gen. David H. Petraeus, published on March 13, 2018, by the venerable Everyman's Library.

A written review of this new translation is forthcoming and will soon be included in our recommendations page, but in the meantime, we would like to introduce you to Peter Harris, an experienced specialist in governance reform, international relations and political and cultural history, with particular reference to China and its neighboring countries.

Born and raised in England, Harris is the Senior Fellow of the New Zealand Contemporary China Research Centre at Victoria University of Wellington, and an Honorary Member of the China Studies Centre at the University of Sydney, Australia.

He was Visiting Professor at the School of Foreign Studies at Nanjing University, Nanjing, China, Director of Asian Studies at Victoria, Senior Fellow at the Centre for Strategic Studies at Victoria, Representative of the Ford Foundation in China, founding Director of the Asia New Zealand Foundation, head of the BBC Chinese Service, and head of Asia research at the International Secretariat of Amnesty International.

He earned a BA (1st Class Honors) in Chinese and an M Phil in International Relations from the University of Oxford.

Peter Harris has published widely on Chinese and Asian affairs in numerous books and scholarly articles. They include China at the Crossroads: What the Third Plenum means for China, New Zealand and the World (Wellington: Victoria University Press for the New Zealand Contemporary China Research Centre, 2014), Concept Papers and Opinion Brochures on Key Democratic Reform Issues(Almaty and Washington DC: USAID and Counterpart, 2010), Three Hundred Tang Poems (London and New York: Penguin Random House/Alfred A Knopf, 2009), The Travels of Marco Polo (London and New York: Penguin Random House/Alfred A Knopf, 2008), and Zhou Daguan’s Record of Cambodia: The Land and its People (Chiang Mai: Silkworm Press with the University of Washington Press, Seattle, 2007). Zhou Daguan’s Record of Cambodia, on a Chinese envoy’s first-hand account of the civilization of Angkor, was named an Outstanding Academic Title for 2008 by the US scholarly journal Choice.

He is currently working on a new annotated translation of the Chinese reformer Liang Qichao's The Doctrine of Renewing the People (xin min shuo) in collaboration with Yi Diandian and others.

Sun Tzu's Art of War translated by Peter Harris (Click on book to buy)

Sun Tzu's Art of War translated by Peter Harris (Click on book to buy)

In addition to his extensive academic credentials, Peter Harris is a life-long enthusiast of the music of Johann Sebastian Bach. Even more telling than his love of Bach is his decades of humanitarian work in places like Vietnam, Cambodia, Indonesia, Kazakhstan, and India. His magnanimous service tells us much about his character, well suited for his adept ability to translate Sun Tzu's Art of War, a book of wisdom and benevolence.

Since Sun Tzu's Art of War is a military work, it would seem logical that the very first English translation came from British Royal Field Artillery (R.F.A.) Lieutenant-Colonel Everard Ferguson Calthrop. The title of his book was Sonshi as it was written with Japanese collaboration and published in Tokyo in 1905 by Sanseido. It was later re-titled The Book of War, published in London in 1908 by John Murray. Sadly, on December 19, 1915, Col. Calthrop died in action on the Western Front (World War I) at only 39 years old.

Fast forward to 1963, when a retired US Marine Corps Brigadier General Samuel B. Griffith published another original English translation of The Art of War with a Foreword by the dynamic British Captain B. H. Liddell Hart.

Gen. Griffith specifically mentions in his book how Col. Calthrop's work was unfairly treated by a certain sinologist given it was a ground-breaking translation in addition to his decorated military background. Likewise, it was Gen. Griffith's military background that drew many modern Western military leaders to Sun Tzu. So it was Gen. Griffith's book where most American generals today are introduced to Sun Tzu, especially for those in the US Marine Corps.

With each passing of baton, from Calthrop to Griffith to Harris, we at Sonshi can see the connected progression in not only the accuracy, clarity, and scholarship, but also in the continuation of The Art of War's relevance in the military tradition firmly rooted in honor, respect, and sacrifice. We believe in short time Harris's Art of War edition will be the standard in every Western military academy and required professional reading list for many decades to come.

Below is our interview with Peter Harris. Enjoy!

Since Sun Tzu's Art of War is a military work, it would seem logical that the very first English translation came from British Royal Field Artillery (R.F.A.) Lieutenant-Colonel Everard Ferguson Calthrop. The title of his book was Sonshi as it was written with Japanese collaboration and published in Tokyo in 1905 by Sanseido. It was later re-titled The Book of War, published in London in 1908 by John Murray. Sadly, on December 19, 1915, Col. Calthrop died in action on the Western Front (World War I) at only 39 years old.

Fast forward to 1963, when a retired US Marine Corps Brigadier General Samuel B. Griffith published another original English translation of The Art of War with a Foreword by the dynamic British Captain B. H. Liddell Hart.

Gen. Griffith specifically mentions in his book how Col. Calthrop's work was unfairly treated by a certain sinologist given it was a ground-breaking translation in addition to his decorated military background. Likewise, it was Gen. Griffith's military background that drew many modern Western military leaders to Sun Tzu. So it was Gen. Griffith's book where most American generals today are introduced to Sun Tzu, especially for those in the US Marine Corps.

With each passing of baton, from Calthrop to Griffith to Harris, we at Sonshi can see the connected progression in not only the accuracy, clarity, and scholarship, but also in the continuation of The Art of War's relevance in the military tradition firmly rooted in honor, respect, and sacrifice. We believe in short time Harris's Art of War edition will be the standard in every Western military academy and required professional reading list for many decades to come.

Below is our interview with Peter Harris. Enjoy!

Sonshi: Welcome to Sonshi. We appreciate your time and being with us today.

Harris: First I want to thank you, Sonshi, for noticing my translation of Sun Tzu's Art of War. I have a high regard for Sonshi and its work and am very pleased by your interest.

Sonshi: Gen. David Petraeus wrote the Foreword to your Art of War edition where he mentioned and illustrated several times how Sun Tzu's Art of War remains relevant today despite it being written 2500 years ago. In your Introduction, you echoed the same sentiment. Why is this ancient work still useful in the modern world?

Harris: In my view Sun Tzu's Art of War is still relevant to the modern world, particularly in certain military situations (notably those involving close encounters in complex terrains), but more generally as well, because of its subtle discussions of deception, planning, and manoeuvre as part of the art of strategy. Its emphasis on and use of deception, a core element of strategy for thousands of years, is particularly important. Of course strategy can be applied in many walks of life, not just warfare, but Sun Tzu's focus is resolutely military. Besides all this, though, The Art of War a fascinating and finely written classic, and endures for all ages and places.

Sonshi: There have been many great original Art of War editions published over the last 30 years. What is different or necessary about your edition published by Everyman's Library?

Harris: In English there have been various original editions, a few great, some less so, in my view. As far as my edition is concerned, Everyman's Library and I agreed that there would be room for a new prose translation in up-to-date English, readable and accessible to the general reader, one that hews closely to the meaning of the original. We agreed that the translation should be accompanied by extracts from the traditional Chinese commentators, with other editorial comment kept separate so that the anglophone reader could have as uninterrupted an experience of Sun Wu's Art of War as possible, and one comparable to the experience of a serious reader in Chinese.

For my part I wanted to offer a text that treated the book primarily as a military textbook rather than one overlaid with Daoist precepts.

Sonshi: You mentioned that the Silver Sparrow Mountain archaeological discovery offered us a new take on the concubine story in which two of Sun Tzu's men were executed instead of the King of Wu's two women, perhaps adding more doubt to Sima Qian's version. Do you believe the story is a fabrication? Does the story reconcile well with the concepts found in The Art of War?

Harris: Standing on its own in The Records of the Grand Historian 史記, with no accompanying biographical material, the story seems odd and far-fetched. Who knows whether it is a fabrication? The existence of two versions of it makes that likelihood neither greater nor less. The story illustrates two ideas in The Art of War - that a general should strictly command the loyalty of his troops, and that a ruler should not engage in day-to-day command over his troops. But as told it reads like a bit of a caricature of these qualities.

Sonshi: Does it trouble you that Sun Tzu wasn't mentioned in The Commentary of Zuo, which raises questions of his own existence? If Sun Wu never existed, should that affect how readers view or approach The Art of War?

Harris: It concerns me, yes. I have an open mind as to Sun Wu's existence, while being sceptical (as many are) of traditional accounts of him. His absence from the Commentary of Zuo (or Record of Zuo 左傳) is puzzling, and seems to me to add to the armoury of those arguing he never existed. But I still think that substantial parts of The Art of War read as if they are from a single hand, or possibly a small group of writers. Quite who we clearly don't know.

Regarding your other question, I don't think doubts about Sun Wu's existence as traditionally construed should greatly affect a reader's approach to the text. After all, we read Zoroaster and Homer and Lao Zi 老子 without being sure of their authorship, or whether they were written by a single person. Problems only arise sometimes when there are glaring inconsistencies within any given text, and that's not a big issue with Sun Tzu.

Sonshi: Did you have any challenges while translating Sun Tzu's Art of War? If so, can you share with us an example or two?

Harris: Many! The text is a difficult one, and no one tackling it should pretend otherwise.

From the outset it raises numerous problems of interpretation that relate to meaning, syntax, ordering, and the likely corruption of particular characters or phrases. Only a fully fledged philological, etymological and linguistic analysis of the kind called for by D. C. Lau (劉殿爵) in his masterly review long ago of Samuel Griffith's translation will be able to address such issues.

Meanwhile my main challenge or concern was to render the text readably but consistently, and as true as possible to the various versions available to us. I took a few risks, for example in the rendition of phrasing ending '...zhe 者' (which I rendered 'if you...' rather than 'he who...'), and in unorthodox translations of difficult terms such as xing形 and shi 勢. The latter is particularly intractable, as I explained in an editorial note, and as other translators have recognised.

Now and then questions were also raised by conceptions of commentators, especially later ones, that had evidently evolved over the centuries and differed from the original.

Sonshi: The popularity of the Thomas Cleary and Denma translations has highlighted Sun Tzu's humanistic principles, which translators such as John Minford at least partly disagree. To some, it is a work of cold ruthlessness. Based on your research and evaluation, where in this wide spectrum do you fall?

Harris: I gather from John Minford (a near-contemporary of mine at Oxford) that his version is very popular too. My view is that The Art of War is primarily a work on military strategy, so that deception inevitably plays a large part in its underlying thinking. So too do the many hard-headed and often expedient measures needed to secure victory in war. I believe highlighting ostensibly humanistic principles in the book quite misunderstands its basic assumptions and purpose.

Sonshi: From your experience, is there a difference between how East Asians view The Art of War and how Westerners view it? If so, what is the biggest difference you see?

Harris: 'East Asians' and 'Westerners' are large categories - too big for me to talk to, really. Anyway - in my limited experience the Chinese view of the work (I cannot speak for Korea or Japan) tends to hold the military and military-strategic aspects of Sun Tzu in higher regard, or perhaps I should say even higher regard, than Western readers and users. That's one reason why Gen David Petraeus's foreword to my edition is helpful. Otherwise, Sun Tzu is often associated nowadays with crafty tactics in other fields, for example in business, and perhaps there's more of tendency to make these associations in the US and Europe than there is in, say, China. But I really don't know.

[End of interview]

Harris: First I want to thank you, Sonshi, for noticing my translation of Sun Tzu's Art of War. I have a high regard for Sonshi and its work and am very pleased by your interest.

Sonshi: Gen. David Petraeus wrote the Foreword to your Art of War edition where he mentioned and illustrated several times how Sun Tzu's Art of War remains relevant today despite it being written 2500 years ago. In your Introduction, you echoed the same sentiment. Why is this ancient work still useful in the modern world?

Harris: In my view Sun Tzu's Art of War is still relevant to the modern world, particularly in certain military situations (notably those involving close encounters in complex terrains), but more generally as well, because of its subtle discussions of deception, planning, and manoeuvre as part of the art of strategy. Its emphasis on and use of deception, a core element of strategy for thousands of years, is particularly important. Of course strategy can be applied in many walks of life, not just warfare, but Sun Tzu's focus is resolutely military. Besides all this, though, The Art of War a fascinating and finely written classic, and endures for all ages and places.

Sonshi: There have been many great original Art of War editions published over the last 30 years. What is different or necessary about your edition published by Everyman's Library?

Harris: In English there have been various original editions, a few great, some less so, in my view. As far as my edition is concerned, Everyman's Library and I agreed that there would be room for a new prose translation in up-to-date English, readable and accessible to the general reader, one that hews closely to the meaning of the original. We agreed that the translation should be accompanied by extracts from the traditional Chinese commentators, with other editorial comment kept separate so that the anglophone reader could have as uninterrupted an experience of Sun Wu's Art of War as possible, and one comparable to the experience of a serious reader in Chinese.

For my part I wanted to offer a text that treated the book primarily as a military textbook rather than one overlaid with Daoist precepts.

Sonshi: You mentioned that the Silver Sparrow Mountain archaeological discovery offered us a new take on the concubine story in which two of Sun Tzu's men were executed instead of the King of Wu's two women, perhaps adding more doubt to Sima Qian's version. Do you believe the story is a fabrication? Does the story reconcile well with the concepts found in The Art of War?

Harris: Standing on its own in The Records of the Grand Historian 史記, with no accompanying biographical material, the story seems odd and far-fetched. Who knows whether it is a fabrication? The existence of two versions of it makes that likelihood neither greater nor less. The story illustrates two ideas in The Art of War - that a general should strictly command the loyalty of his troops, and that a ruler should not engage in day-to-day command over his troops. But as told it reads like a bit of a caricature of these qualities.

Sonshi: Does it trouble you that Sun Tzu wasn't mentioned in The Commentary of Zuo, which raises questions of his own existence? If Sun Wu never existed, should that affect how readers view or approach The Art of War?

Harris: It concerns me, yes. I have an open mind as to Sun Wu's existence, while being sceptical (as many are) of traditional accounts of him. His absence from the Commentary of Zuo (or Record of Zuo 左傳) is puzzling, and seems to me to add to the armoury of those arguing he never existed. But I still think that substantial parts of The Art of War read as if they are from a single hand, or possibly a small group of writers. Quite who we clearly don't know.

Regarding your other question, I don't think doubts about Sun Wu's existence as traditionally construed should greatly affect a reader's approach to the text. After all, we read Zoroaster and Homer and Lao Zi 老子 without being sure of their authorship, or whether they were written by a single person. Problems only arise sometimes when there are glaring inconsistencies within any given text, and that's not a big issue with Sun Tzu.

Sonshi: Did you have any challenges while translating Sun Tzu's Art of War? If so, can you share with us an example or two?

Harris: Many! The text is a difficult one, and no one tackling it should pretend otherwise.

From the outset it raises numerous problems of interpretation that relate to meaning, syntax, ordering, and the likely corruption of particular characters or phrases. Only a fully fledged philological, etymological and linguistic analysis of the kind called for by D. C. Lau (劉殿爵) in his masterly review long ago of Samuel Griffith's translation will be able to address such issues.

Meanwhile my main challenge or concern was to render the text readably but consistently, and as true as possible to the various versions available to us. I took a few risks, for example in the rendition of phrasing ending '...zhe 者' (which I rendered 'if you...' rather than 'he who...'), and in unorthodox translations of difficult terms such as xing形 and shi 勢. The latter is particularly intractable, as I explained in an editorial note, and as other translators have recognised.

Now and then questions were also raised by conceptions of commentators, especially later ones, that had evidently evolved over the centuries and differed from the original.

Sonshi: The popularity of the Thomas Cleary and Denma translations has highlighted Sun Tzu's humanistic principles, which translators such as John Minford at least partly disagree. To some, it is a work of cold ruthlessness. Based on your research and evaluation, where in this wide spectrum do you fall?

Harris: I gather from John Minford (a near-contemporary of mine at Oxford) that his version is very popular too. My view is that The Art of War is primarily a work on military strategy, so that deception inevitably plays a large part in its underlying thinking. So too do the many hard-headed and often expedient measures needed to secure victory in war. I believe highlighting ostensibly humanistic principles in the book quite misunderstands its basic assumptions and purpose.

Sonshi: From your experience, is there a difference between how East Asians view The Art of War and how Westerners view it? If so, what is the biggest difference you see?

Harris: 'East Asians' and 'Westerners' are large categories - too big for me to talk to, really. Anyway - in my limited experience the Chinese view of the work (I cannot speak for Korea or Japan) tends to hold the military and military-strategic aspects of Sun Tzu in higher regard, or perhaps I should say even higher regard, than Western readers and users. That's one reason why Gen David Petraeus's foreword to my edition is helpful. Otherwise, Sun Tzu is often associated nowadays with crafty tactics in other fields, for example in business, and perhaps there's more of tendency to make these associations in the US and Europe than there is in, say, China. But I really don't know.

[End of interview]